Six Images

As a visual artist I have tried to use my photography as a way to express my concerns about institutionalized racism, injustice, and bigotry towards the marginalized and unrepresented of the world. I believe art and artists have a role to raise consciousness and awareness about injustice in the world, to speak truth to power and to be instruments of change.

I seek to provoke a reaction from the viewer, hopefully for change; positive and enlightened, to make and ensure lasting social justice transformations take place here, in America and around the world. It bears repeating because it is often forgotten that indifference, intolerance, bigotry, and injustice—all gain a foothold when people are convinced that those they fear are not human beings in the first place. We all belong.

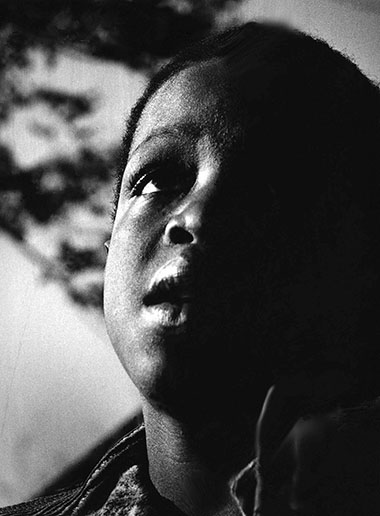

A few days after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis on April 4, 1968, I ventured out into the Greenwood area hoping to find a subject that expressed my feelings. I was both angry and saddened by his death. I wanted an image that captured what Black Americans were facing going forward. I found this young boy sitting on a curb by himself. I struck up a conversation with him. He consented to pose for me. The expression on his face seemed to express hope or was it hopelessness?

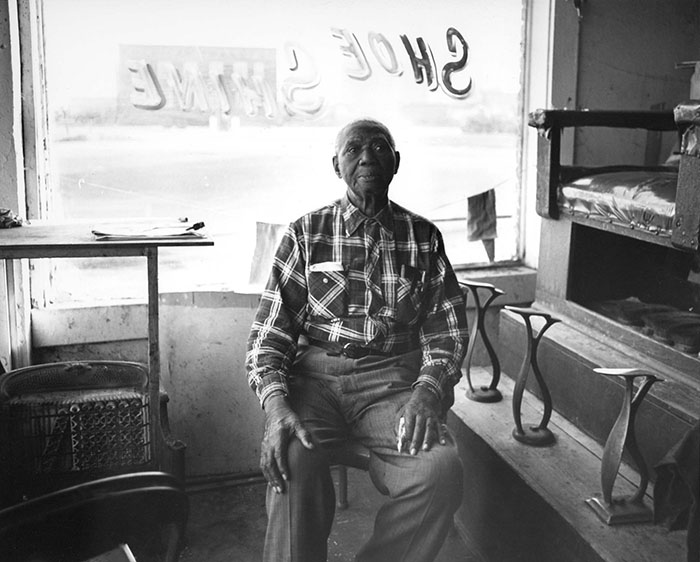

Mr. Smith, owner of the Shoe Shine Parlor at the corner of Greenwood and Archer was one of a handful of businesses still left on Greenwood. Most were boarded up awaiting the bulldozers. As I photographed him, he told me his business would not be around much longer. He felt the city was determined to eliminate it. Days later I went by. Mr. Smith was gone, and his business was boarded up.

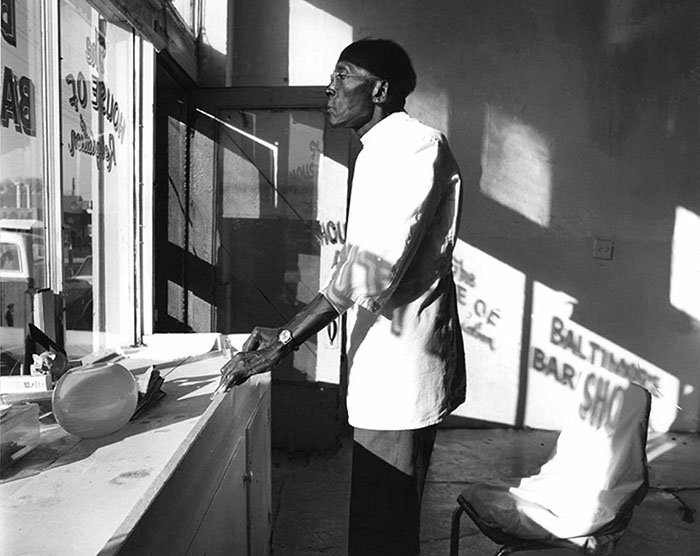

Mr. Dave Gardner had one barber chair in his small shop on Greenwood Avenue. He sat alone as I walked in. We began conversing about Urban Renewal and how they were systematically destroying businesses and people's livelihoods. I asked him his plans. He told me he had none. "I have been doing this for twenty-five years. I cannot start over, I am too old." I asked him if he wouldn't mind posing for me; he consented. He stood, a furlong look on his face as he stared out the window at the bulldozers as they razed another business across the street. The next day I came by to check on him. The Baltimore Barbershop was bulldozed over. I never saw Mr. Gardner again.

This image, to me, depicts the second destruction of Greenwood. It shows a boarded-up Greenwood Avenue in 1978, fifty-seven years after the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre which left over three hundred killed, countless injured and over 10,000 homeless. During the 1970s, instead of a white mob's invasion of Greenwood, this time it was the city's desegregation of public housing and accommodation, 1970s economic recession, and the intrusion of an expressway through the heart of the business section, all contributing to Greenwood lying dormant. In the mid 70s the city of Tulsa declared the Greenwood area a Ghetto, paving the way for so-called Urban Renewal and Eminent Domain, to finish what began in 1921.

Dedicated in 2010, the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park is dedicated to the victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The park was named in honor of Rentiesville and Tulsa native Dr. John Hope Franklin, distinguished historian, educator, and civil rights activist. Dr. Franklin's father, B.C. Franklin, a Tulsa lawyer, was instrumental in stopping the city of Tulsa from enforcing a Fire Ordinance to prevent Black people from rebuilding after the Massacre. The sculptures were designed and built by nationally known African American sculptor Ed Dwight. Several plaques throughout the park provide a history of Black people in Oklahoma before and after statehood.

Ellis Walker Woods was the first principal of Booker T. Washington High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Born in 1885, the son of freed slaves in Mississippi, Woods served as a principal from 1913 to 1948. After graduation from Rust College in Mississippi, Woods heard Oklahoma needed Black teachers. Woods walked over four hundred miles from Memphis, Tennessee. Arriving in Oklahoma, he accepted a teaching position in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. He often encouraged his students with these words: "You're as good as ninety percent of all people and better than the other ten."

The memorial is located on the Oklahoma State University Tulsa campus where the original Booker T. Washington High School once stood. Dedicated in 2019, the memorial was the brainchild of Booker T. Washington alumni Edgar and Captola Dunn, and Richard Gipson.

Don Thompson is a fine arts photographer living in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He has works on display at the Smithsonian Museum of African American Culture and History, Washington D.C., the permanent collection of the Philbrook Museum, and Oklahoma State University, Tulsa. He is an author, curator, historian, speaker, and community activist. He is married to Barbara Eikner Thompson.

All images remain in the ownership of Don Thompson and are copyrighted under the laws of the United States of America. They are for usage of this issue of Passage only.