Triumphal Entry into Gonzales

As a painter who became severely sensitive to chemicals several years ago, I was already familiar with feeling shuttered and shut down—emotions the pandemic has caused many to experience. In my case, my fate appeared to be that I would never again do the work I loved—I would not paint again.

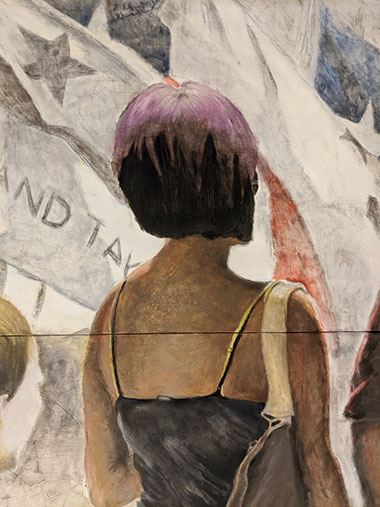

Triumphal Entry into Gonzales, a work in progress that will be displayed at the Robert Lee Brothers Memorial Library in Gonzales, Texas, is the culmination and celebration of my discovery of a safer method to paint. It is a massive 9 feet by 35 feet oil painting in 14 panels, done with one tube of brown paint (life is dirty) and a few squirts of color—smeared, scumbled, and scraped until scarring the canvas' surface (life is brutal).

Drawing on events in local history when defeat seemed inevitable, the narrative begins in 1831. Mexico loaned the Texian and Tejano immigrants in the wilderness north of their border a small cannon to defend themselves. But, as tensions escalated, Mexico asked that the cannon be returned. Instead, the settlers fired the first shot for Texas Independence, raising a small flag handstitched from a white wedding dress and painted with the black image of a cannon, a star, and the defiant words "Come and Take It." Tensions finally exploded, and the Texian troops met the Mexicans head-on at the Mission San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo) where, sadly, 32 brave volunteer soldiers from Gonzales were slaughtered along with many others, including legendary frontiersman, Davy Crockett, from Tennessee. Left suddenly alone on the frontier, the widows and orphans of the dead ran barefoot screaming and sobbing through the prairies just ahead of the bloodthirsty victors. Soon afterwards, the Texians rallied, and, with a fierce battle cry, went on to win independence from Mexico in 1836. An annual Gonzales celebration recalls these events and includes a battle reenactment and a colorful parade, which I depict. Besides the historical allusions in the painting, many other levels of meaning coexist.

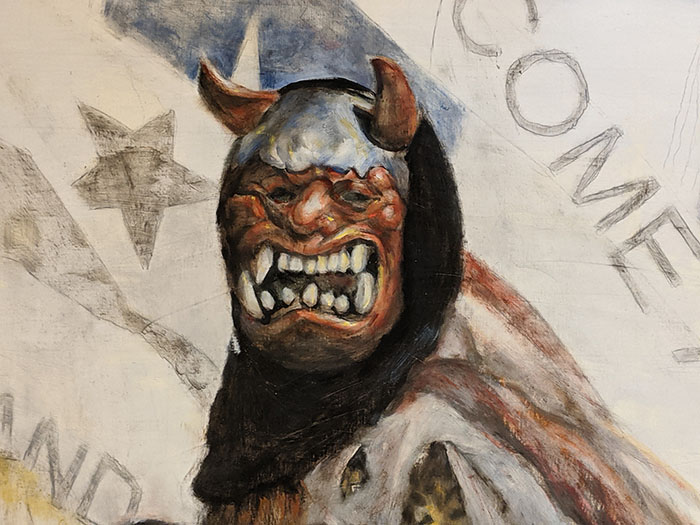

In my mural, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the President of Mexico and later the cruel general in the battles of Gonzales, Goliad, and the Alamo, lives once again and marches in full-military regalia through the streets of present-day Gonzales, echoing his earlier triumphal trampling of Gonzales' charred remains. The Texian patriots are also resurrected and appear in the painting, along with around 50 other figures. Lining the parade route on a cool, sun-dappled morning, are the curious, young and old, who have come to get lost in lightheartedness for a while. A disabled World War II veteran waves a tiny American flag in the shadowy foreground. A paralytic boy watches from his rollator-walker. Also present in the scene are those with memory loss, developmental delays, obesity, autism, cancer, PTS, immunodeficiency, orthopedic devices, catheter bags, cerebral palsy, pacemakers, rheumatoid arthritis, and clinical depression—we are all there—those with hope and those with none. Snaggle-toothed Satan and his assistants from Iglesia Sagrada Corazon (Sacred Heart Church) chuckle and swirl in the middle of the street, while Christ with his cross, the symbol of self-sacrifice, slips through the crowd unnoticed. Lovely ladies with a blotchy skin disease cha-cha-cha to recorded music. While some onlookers, never far from technology, check cell phones at every chance for a quick fix, an avid reader, absorbed in a book, is oblivious to, or perhaps reading about, the entire drama at hand. As enthusiasm builds, "Come and Take It" flags wave into a frenzy.

Dating to at least ancient Rome, the theme of a triumphal entry is not a new one and informs my painting in numerous ways. The oldest reference here is to Christ's entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday 2,000 years ago when welcomed by the Jews as the long-expected Messiah, or Savior of the world. Much later, Rembrandt depicts a celebratory scene with Captain Frans Banning Cocq and his militia, in 1642, triumphantly "entering" Amsterdam in The Night Watch; Ensor paints Christ "entering" contemporary Brussels in 1889, in a carnivalesque parade; and Monet depicts an 1878 patriotic "entry" into Rue Montorgueil in Paris, with French flags flying—all portraying achievements or victories.

The first sketches for my mural did not include flags, but rather a clear-blue sky. During that period of my life, like the widowed immigrants of Gonzales, I was exhausted from crying for help. With each life-changing diagnosis, every heartbreak and goodbye, flags became essential—Texan, American, Mexican, and Come and Take It—until flags completely crowded out the sky and flapped hysterically as if to dry, or defy, the tears spent.

Through motifs not always obvious in my work, I examine universal human themes derived from everyday occurrences in the lives of ordinary people. Our ordinariness. I prefer realism because life is so hard . . . and so real. None of us escapes the harshness—the uncertainties and the certainties, whether in times of a pandemic or not. The shock. The loss. The brokenness.

My work is a response to this all-encompassing reality. For a time, distractions, such as parades, will stop the misery of which no one is exempt. Despite our interracial, intergenerational, and multi-cultural differences, as well as mental and physical ones, we have the commonality of an approaching end. We are all immigrants in places we never thought we would be. How can we be delivered from the darkness? We have much to learn about the significance of human life—about the Light blazing within and around us. About passionate love for others. Through my work, one might have an opportunity, I would hope, to once again reflect. Even if crushed and broken, we can raise a flag. We can welcome our uniqueness with gratitude, as we weave lives together, bridge cultural differences, and strive for a better, united future. And, in so doing, we might even be surprised by joy—and by little pockets of exuberance.

Ida H. McGarity lives and works in Gonzales, Texas.