Woodlands

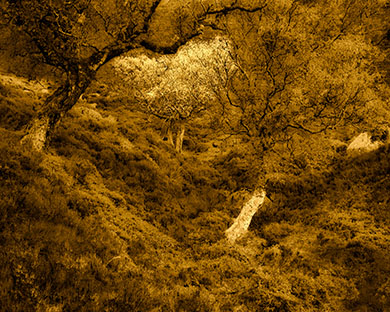

The Woodlands project began when I found myself walking through a densely wooded park, Periwinkle Grove, near Stonehaven, Scotland. It was an intimate, calm place. The seaside light that day was bright, soft, and close. It triggered memories of a light much sharper and more expansive, the light of West Texas desert and mountains. It was in the Big Bend region where I realized that how a place feels, rather than the way it looks, was important to me. I began to understand that observation is not enough; it is important to consider, to wonder, how things are the way they are.

"How" is an intriguing question. I often think about it when processing and printing an image, and always when photographing. What determines how I respond to a place? Is it my decision alone or are there other intangibles in play? Why are there places I don't want to leave and places I've refused to spend the night? I've broached that question with others who've spent time alone in the wilderness and (usually after a few beers) will hear stories that resonate with mine. Is it intuition? If so, how is intuition informed by place? Can places have, or somehow contain, memory? Do they have history beyond the physical and how would that be expressed? After forty years I still do not have answers, but the question is enough.

Over time my approach to printmaking has become increasingly idiosyncratic. I'm trying to understand the link, the through line, that connects the experience of a place in time with making an emotionally authentic print of that experience. Each image in the Woodlands project is processed and printed on its own terms. Given the time and attention it deserves, an image will tell me how it should be realized as a print. All I need to do is listen. Sometimes I'll envision how an image might be printed when the exposure is made, but I am often wrong. Images captured the same day, from the same place, may be interpreted very differently. There are no rules.

Like other photographers of a certain age, my printmaking apprenticeship began with silver gelatin in the wet darkroom. I was fortunate; the bar was set dauntingly high among my colleagues, peers, and early heroes. That early discipline and experience informed and guided my transition to digital imaging. I was an early adopter, not because I love the technology, complexity, or cost (I do not), but because I wanted to work with ink on paper. In graduate school I had been given access to a complete set of Alfred Stieglitz's Camera Work. The photogravures, hand-tipped onto the magazine's pages, challenged my understanding (and prejudice) of what a photographic print could be. The photogravures were softer, atmospheric, and deeper than the hard-edged silver gelatin prints I was working so hard to perfect. For the first time I began to think about how light interacts with a print, and how that interaction affects perception.

I investigated traditional copperplate photogravure from the early 1980s but rejected it. The internet didn't exist, information and expertise were hard to find, and I wanted nothing to do with the chemistry the process required. I began experimenting with silver gelatin, finding ways to push the prints in a different direction. It was a rich and formative time for me. Then, in 1994, Epson introduced their first consumer inkjet printer. The size of a toaster, it held four inks and was limited to letter size paper. I finally had a way to make prints with ink on paper and never looked back.

As my approach to printing with ink matured, I often thought about the Camera Work photogravures. They were a constant subliminal and disruptive reminder that there were prints I had not made yet. That changed with the development of photo-polymer gravure (using plates originally developed for industrial printing) and the inkjet direct-to-print (DTP) process. The old was made new again and I started making photogravures.

Prints from the Woodlands project were first exhibited in the Alice and Bill Wright Photography Gallery at the Grace Museum in Abilene, Texas, in 2011. The Grace is a beautiful venue and the Wright's have been committed and generous supporters of photography for many years. It was an honor to exhibit there. All the photographs in the exhibition were toned grayscale prints, originally captured on large format color negative or Polaroid films. These were scanned and processed digitally. Some are what photographers usually call "straight" prints (though I disagree with the premise and find the term misleading). Others are, for lack of a better word, "bent" to alter the line structure and tonal scale of the print. Straight or bent, they all maintain a connection to the perceived world.

The prints were made using inkjet printers with various carbon-based pigment ink sets on a variety of substates: the cotton fiber papers that artists and printmakers have used for over six hundred years, modern papers coated for inkjet printing, ceramic coated polyester-based media, and hand-varnished archival tissue (a printing technique harkening back to the 1840s). The show included images from Scotland, Texas, and Louisiana. Work from Ireland, New Mexico, Utah, and New England has since been added; some made on film but, increasingly, more made with digital cameras. And, of course, photogravure has been added to the mix.

My connection to the work changes as I grow older and one idea or insight, the successes and failures, morph into the next. I've learned that fiddling with my internal compass is a good way to lose clarity and I choose not to consciously direct or control what I photograph next or how an image is interpreted as a print. Making photographs is a lot like playing baseball; you have to relax and concentrate. There is an exquisite tension between what might happen and what will happen. It's a mental space that you embrace, and then learn how to use.

Bill Kennedy is Professor Emeritus of Photography and Media Arts at St. Edward's University in Austin, Texas. He has taught workshops and made presentations for the Maine Media Workshops, the Santa Fe Workshops, the California Arts Institute, Anderson Ranch, the Royal Photographic Society of Scotland, the Society for Photographic Education, the National Press Photographer's Association, and the American Society for Media Photographers. Grants include the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and numerous academic grants. His work is included in the Photography Collection, Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; the Houston Museum of Fine Art; the Ansel Adams Estate archives; the National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland; and the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago.