The Future Lives of Paper

Words and images on paper have a permanence in the physical world that their digital counterparts do not—they might be picked up and read again decades from now, or even centuries. But paper yellows and decays. It might burn or be damaged by water or may simply be lost and forgotten. And the meaning of what is printed on its surface is always shifting, depending on when, and in what context or mindset, it is encountered.

When I first read them, I was startled by the letters my father and his father exchanged during the Vietnam War—startled by my grandfather's earnest pleas for my father to consider the consequences of protesting the draft and my father's manic idealism in the 10-page handwritten letter where he declares himself an artist and announces he is going to forge his own path. Their battle is still so alive in the words in those letters, 55 years later.

But also palpable is the misogyny in the draft of a letter to my mother (was this version actually sent?) in which my father coldly states she is too fat to love. He wrote this before their divorce, before they were even married.

Histories, lives, archives are bound to paper, artifacts made from pressed wood pulp. Paper holds more than we might at first acknowledge—the racist and sexist ideas of the past, stories we may not want to preserve.

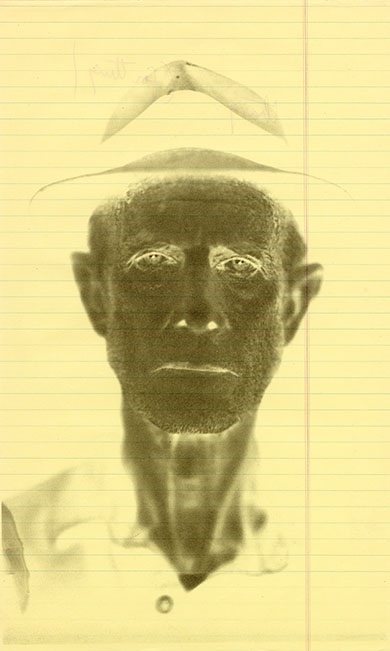

Paper archives are also where people recover, reclaim and restore identities.

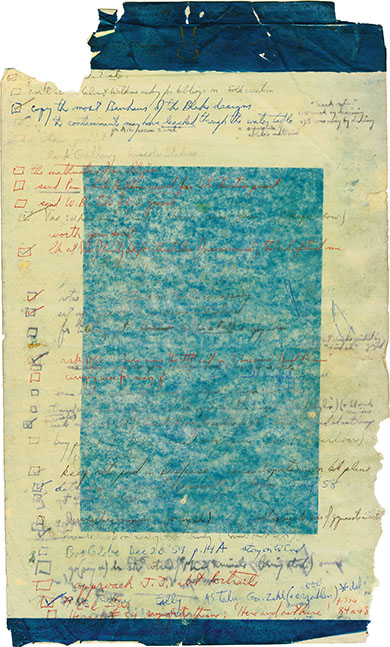

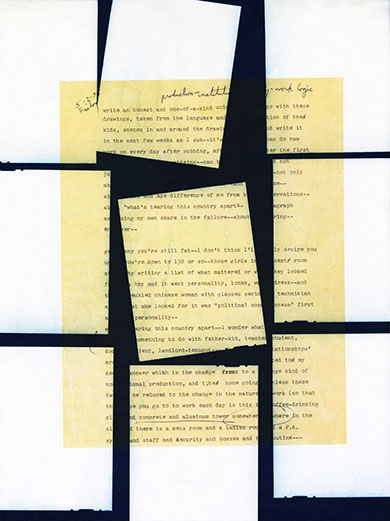

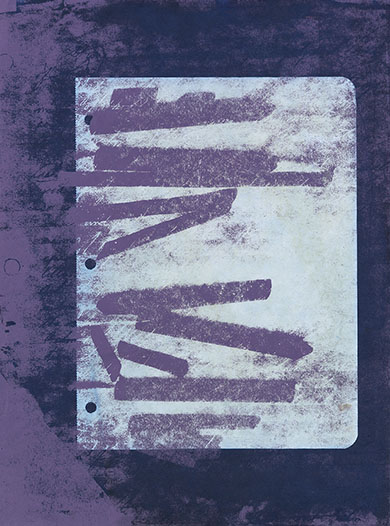

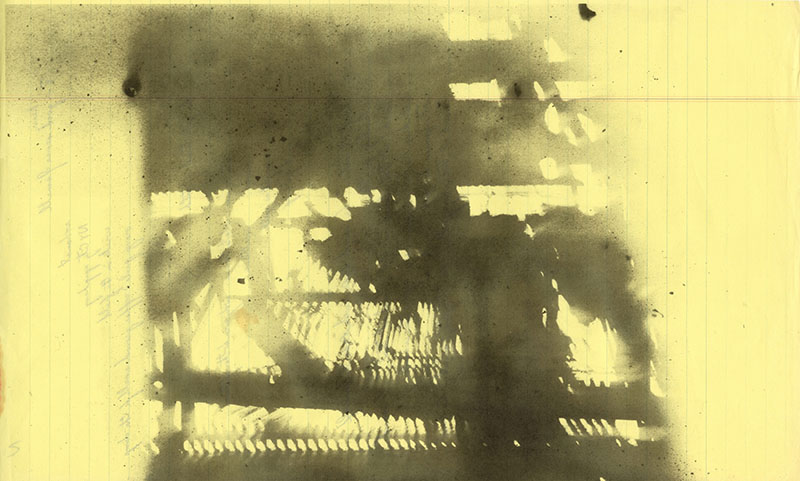

My work is created through physical engagement with documents and photographs. I alter, reproduce, redact, or erase the original documents. I intervene with what is recorded and retained by the paper itself. One of my techniques is to make one document photographically light sensitive with cyanotype chemistry and make a photogram of a second document or image directly on it. These modified papers become fragments through which I recount the story of my unusual upbringing. Meanings double, proliferate, as two or more very different perspectives come to inhabit the same sheet of paper at the same time.

These papers hold my history. I enter history through these papers. They are part of my story, a story to challenge and undo.

In the end, though, they are just paper, tattered remnants of experience, destined ultimately to vanish.

Keliy Anderson-Staley is a Guggenheim Fellow, and her work has been exhibited widely, including at Akron Art Museum, Bronx Museum of the Arts, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Southeast Museum of Photography, Shelburne Museum, Ogden Museum of Southern Art and Morris Museum of Art. Collections holding her work include the Library of Congress, Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Houston Airport System, Museum of Fine Arts Houston and Portland Museum of Art. On a Wet Bough, a monograph of her tintype portraits, was published by Waltz Books in 2014. Documents & Dwellings, a catalog for her solo exhibition at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, was published in 2022. She is an Associate Professor of Photography and Digital Media at the School of Art, University of Houston.